By Nicole Prieto | staff writer

By Nicole Prieto | staff writer

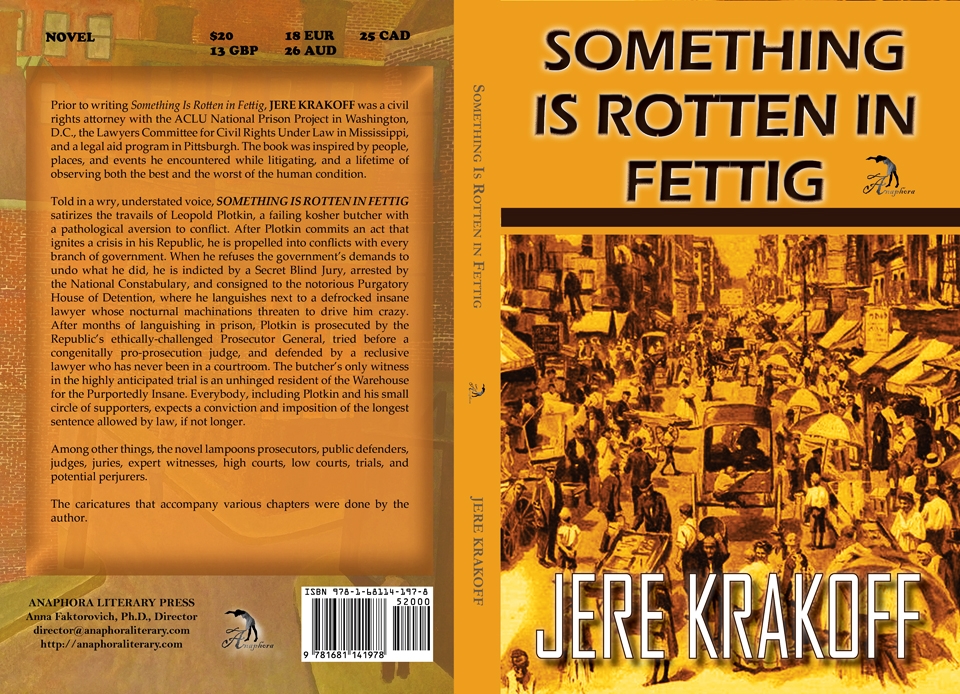

Written by 1964 Duquesne Alumnus and retired Civil Rights Attorney Jere Krakoff, “Something is Rotten in Fettig” is a satire that exhibits a tongue-in-cheek familiarity with the dysfunctions of the legal system. Appropriately, this is a worthy read to undertake just in time for Homecoming (or at least before you consider going to law school).

Leopold Plotkin is a quiet kosher butcher in the city of Fettig, the capital of the esteemed Republic, who tends to his father’s declining business. After a botched attempt at increasing sales, Plotkin, on his parent’s orders, slathers the family butcher shop window with mud to prevent customers from window shopping.

The nonsensical directive soon backfires into a “Mud Crisis” that turns Plotkin into the Republic’s most hated anti-capitalist. Later accused of breaking a law explicitly made for him to be indicted for violating, Plotkin endures the trials, tribulations and humiliations of being a publicly despised “criminal-type” with every card in the system stacked against him.

Plotkin is in the running for contemporary fiction’s most sympathetic human punching bag. He is abused by everyone from ambivalent relatives to corrupt “lawmongers” to unnerving crowds of anti-Semites. As a child, his father quashes his dreams of becoming an intellectual. He is arbitrarily beaten and slapped before, during and after his imprisonment while awaiting trial. All throughout, he is vexed by hypochondria and, per Plotkin family tradition, a disposition for believing in the worst.

Fans of Lemony Snicket’s “A Series of Unfortunate Events” will be at home among the book’s gaggle of willfully blind authority figures. The novel invokes the situational absurdity of works by Franz Kafka, Albert Camus and Jonathan Swift; the cast is loaded with figurative (and literally drawn) caricatures of biased jurists, inflamed mobs and incompetent legislators.

The book’s treatment of judicial formalities is hardly kind. Plotkin is first indicted by a Secret Blind Jury presented with evidence while blindfolded; he has a brush with the Republic’s Society for the Apparent Representation of Indigent Criminal-Types, which prefers to employ unaspiring attorneys who graduated in the bottom of their classes; his actual trial begins with a four-hour “Opening Rant” by the prosecution and concludes with both attorneys’ “Closing Diatribes.”

Krakoff’s prose lays out his dark humor on every page. No passage is superfluous in illustrating his absurd world. At 60 short chapters with a generous epilogue, the book could perhaps stand some shaving on less significant points, such as Plotkin’s awkward meeting with a psychiatrist. Still, its 265 pages keep it a quick read.

The only difficult part of wading through Krakoff’s world is acclimating to the Republic’s point-blank injustices that compound Plotkin’s misery for nine-tenths of the novel. It is impossible not to feel as despondent and helpless as Plotkin in an unpredictable system that discards justice in favor of inflated egos. It is even more depressing when you remember that Krakoff is depicting a world not too far removed from our own.

One of the most impressive features of his writing is the bulk of characters he handles and interweaves in such a short volume. The cast of characters in the beginning of the book, which delineates their roles and relation to Plotkin, is well-warranted. Krakoff draws on his own experiences as a retired civil rights attorney to illustrate these true-to-life exaggerations, and he takes the time to pack in a believable background and motive for each.

Prosecutor General Umberto Malatesta is driven by the glory of litigating a high-profile case in a pro-prosecution court. Malatesta’s de facto co-conspirator, the diminutive Justice Wolfgang Stifel, is eager to live by his maxim “that it’s better for dozens of innocent scum to be unjustly convicted than for one [a—hole] to be unfairly acquitted.”

There is something to be said on how the least self-serving and capable lawmonger among the cast, Prime Thinker Guda Prikash, is a scholarly hermit with a phobia of public speaking — who must be hypnotized before he can even stand in a courtroom. He works for a prestigious firm that serves Fettig’s high society, and which openly delays Plotkin’s advance appointment with his pro bono counsel in favor of catering to the needs of the unscheduled elite.

Ana Bloom, Plotkin’s “only female friend,” is hardly treated as some destined love interest for our despondent hero, and it is her sincere friendship and persistence that leads him to getting adequate legal representation. Ana and the very few allies in Plotkin’s life ultimately make his misery bearable and give him the faintest sliver of hope for an acquittal, however unlikely.

The book is, in the end, a no-holds-barred roast of the U.S. judiciary. No number of formal procedural rules can truly overcome human irrationality and the power of an outraged majority. Grab a copy of this Duquesne grad’s novel — and judge it for yourself.

Thanks for the exceptionally well written book review. I’ve read the book and can attest to the spot-on review you have written. The book is certainly worth the read and your review will help spread the word about this quiet classic on the injustices of our judicial system.