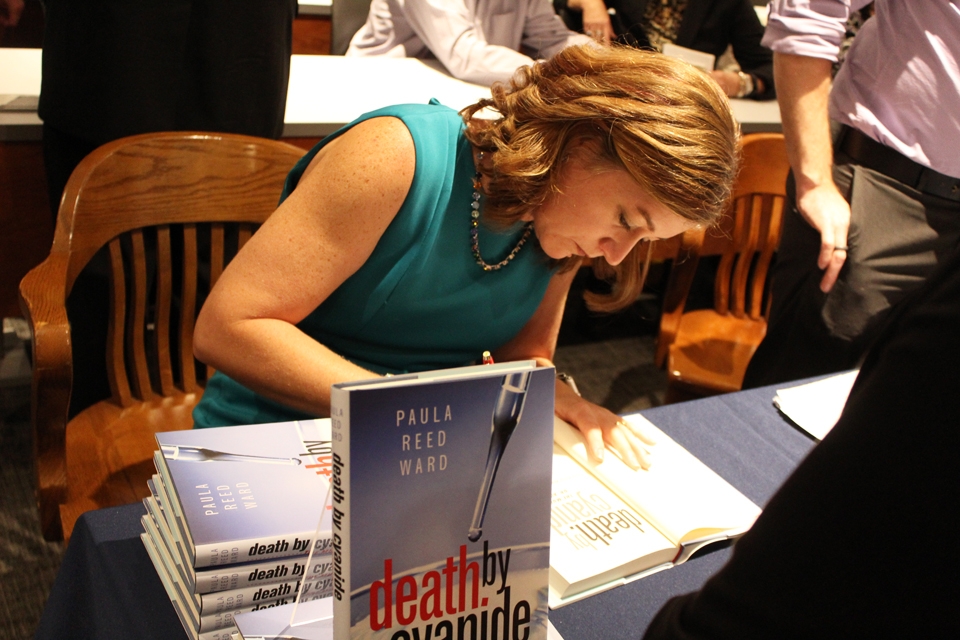

Paula Reed Ward signs a book at an event in the law school on Oct. 4. Ward has taught investigative reporting classes at Pittsburgh universities including Duquesne.

Paula Reed Ward signs a book at an event in the law school on Oct. 4. Ward has taught investigative reporting classes at Pittsburgh universities including Duquesne.

Liza Zulick | Staff Writer

On April 17, 2013, Dr. Autumn Klein collapsed on her kitchen floor and was rushed to the hospital. After three days in the hospital, doctors declared her dead on April 20. Later test results determined the cause of her death to be cyanide poisoning.

Her husband, neuroscientist Robert Ferrante, is serving a life sentence for the first degree murder of his wife.

Now, almost three years after Dr. Klein’s death, a former Duquesne professor with a connection to the case has published a book about the events leading up to, including and following the strange murder.

Paula Reed Ward, a reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette who taught an investigative journalism class at Duquesne last year, visited campus on Oct. 4 to present her nonfiction book, “Death By Cyanide.”

As a reporter for the Post-Gazette at the time of Klein’s murder, Ward wrote a series of articles about Klein’s death and Ferrante’s resulting trial. Those articles form the basis of her book, titled “Death by Cyanide.” Ward used her presentation at Duquesne as an opportunity to promote the book and talk about her investigative process.

The publishing process for “Death by Cyanide” took less than a year, but Ward relied on years worth of background information that she had gathered.

During her research, Ward conducted many interviews with Klein’s family. Ferrante also gave her an interview and answered personal questions about his life and family, but they shied away from talking about his trial.

“I did not ask any tough questions because I already knew he was pleading not guilty,” Ward said. “That would only result in not getting any answers at all.”

She has even spoken to him on the phone twice since his incarceration. Ferrante told her he is now working with organizations while in prison to figure out how his wife’s cyanide test could have produced what he maintains was a “false positive.”

Though Ward has written many investigative pieces during her time with the Post-Gazette, she decided the murder of Autumn Klein was book-worthy because she felt a strong connection to Klein.

“I struggle to balance that work life scale everyday, and I saw in Autumn a similar thing … treating her patients and getting home late in the night to kiss her daughter goodnight,” Ward said.

Pamela Walck, a journalism professor at Duquesne, stressed the importance of investigative journalism and the type of work Ward does.

“At the heart of investigative journalism is the idea that there is an injustice … and the work that investigative journalists do to uncover those wrongs … that work is really critical in terms of helping to hold people accountable for the trust that placed with them,” Walck said.