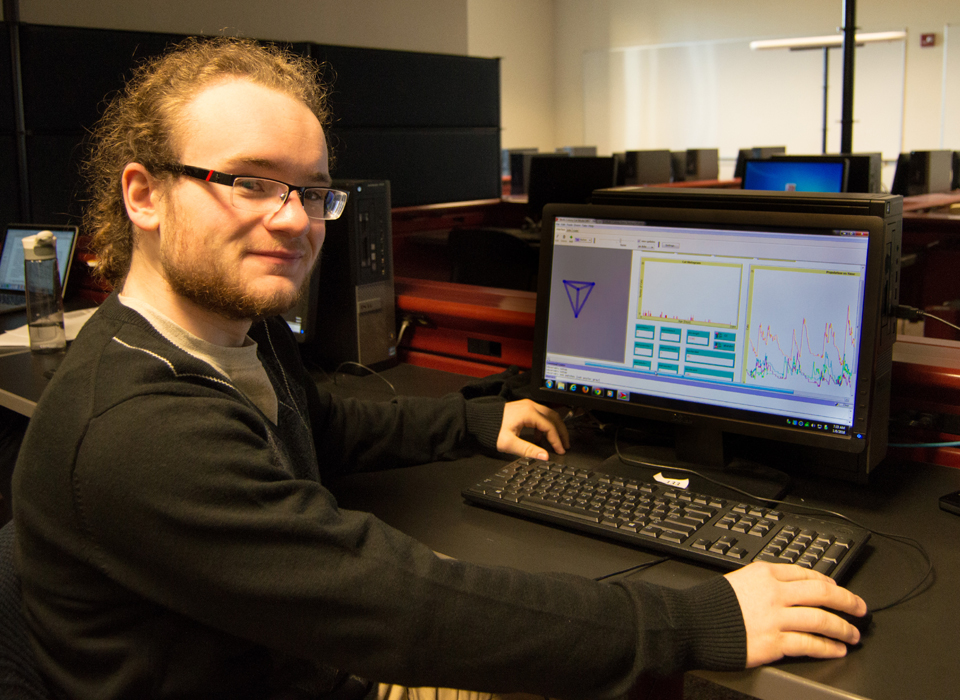

Junior Tim Ireland poses for a photo in a College Hall computer lab. Ireland combined his passion for computer science and physics to model feral cat colonies.

By Brandon Addeo | Asst. News Editor

Duquesne student Timothy Ireland has spent a lot of time thinking about cat pee.

The 19-year-old mathematics and physics major has programmed a computer simulation that shows the behavior, reproduction and spread of virtual wild cat colonies. This simulation can be used by researchers and animal control organizations to learn more about the behavior of feral cat colonies in the real world.

The American Veterinary Medical Association estimates there are 70 million feral, or wild, cats in the United States, only slightly fewer than 80 million domesticated cats. With numbers like these, cat overpopulation is a serious problem in some areas.

According to Ireland, these feral cats can transmit dangerous diseases such as rabies to humans and pets alike.

“And they annoy people, too,” Ireland added, through behaviors such as spraying urine, yowling and fighting.

Ireland’s simulation, created with the help of Duquesne math professor Rachael Neilan, visually represents feral cat populations on a digital map and accounts for those “nuisance” variables, as well as factors such as gender, movement between cat colonies, births and deaths.

The program uses these variables to pit the effectiveness of neutering male cats against performing vasectomies and hysterectomies on both male and female cats, and how the nuisance behaviors are affected by each method.

Neutering proved to be more effective at eliminating nuisance because it stops hormone production — the source of the undesirable behaviors.

“Using our model, we found that both [methods] are satisfactory methods for reducing the growth of feral cat populations,” Neilan said. “However, [neutering] is substantially better … at reducing public nuisance.”

In other words, Ireland and Neilan found that hormonal cats still pee on things and get in fights, while cats with limited hormone production behave better.

The computer program could potentially have real-world applications.

Janice Bernard, program director of Pittsburgh’s Animal Rescue League, said that while the Animal Rescue League has never used a simulation program like Ireland’s, they would “absolutely” consider it.

She added that while there is no estimate of the number of feral cats in the city, the Animal Rescue League does sometimes get calls from residents asking for help with large groups of feral cats.

Ireland also said that his feral cat model could be used, with some adjustments, in populations of other animals, such as deer.

Ireland first began the project in a mathematics service learning class in the fall 2014 semester. Neilan worked closely with him to design the model and eventually secured a grant for the project.

He said part of the reason he chose feral cats as the topic of his service learning project is because his father is a veterinarian.

“It was something I was already familiar with, happy to jump into ,and it seemed like an opportunity to learn some interesting new skills,” Ireland said.