By Julian Routh | Editor-in-Chief

“The Cost of College” is an ongoing series that will examine what it really costs to get an education. This week’s story explores

the rising cost of college textbooks, which have surged by more than 1,000 percent since 1977.

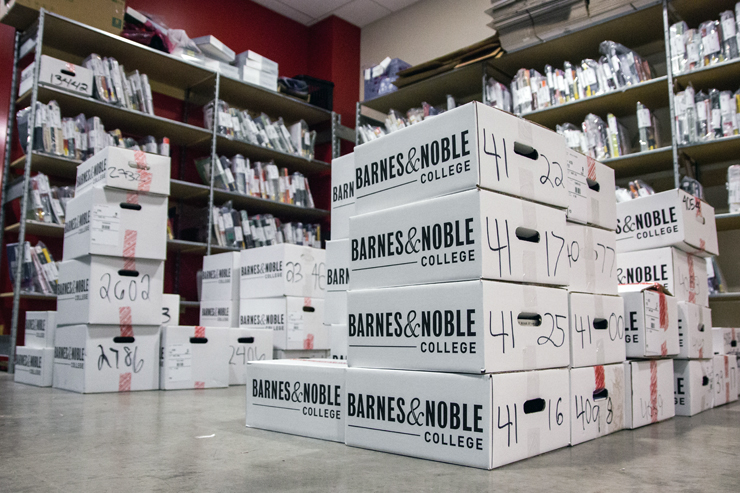

In the basement of the Barnes and Noble bookstore on Forbes Avenue earlier this week, troves of students perused through the aisles to purchase textbooks for classes this semester.

But in a fit of solemn rage, sophomore economics major James Daher put a copy of “Modern Business Statistics” back on the shelf.

“My professor emailed me last night and said we needed this for the first day of class today,” he said. “It’s $147 to rent, which is ridiculously overpriced. I’ll just look online.”

Daher – who said his books cost more than $1,000 this semester alone – is one of many students fed up with textbook prices who are looking elsewhere for more affordable options.

Although textbook prices have surged, the popularity of book rentals and buying from used sellers like Amazon and Chegg is on the rise as well.

According to an NBC review of Bureau of Labor Statistics data, textbook prices rose more than 1,041 percent from January 1977 to June 2015, or three times the rate of inflation. CollegeBoard estimates the average yearly books and supplies cost for full-time undergraduate students at four-year colleges to be around $1,200.

But neither of those estimates includes thwe used book or rental markets, which are thriving. More than a third of students rented at least one textbook during the last academic semester, up from about a quarter the year before, according to the National Association of College Stores.

The association also estimates that – with both used books and rentals considered – college students spend about $638 a year on course materials, an amount much less concerning for students on a budget.

Barnes and Noble – which has been Duquesne’s official campus bookstore since the mid-1980s – launched its rental program in 2012, allowing students to rent books for less than 50 percent of the cost of purchasing a new textbook.

Choosing textbooks for each course is entirely up to the faculty, Duquesne spokeswoman Bridget Fare said.

Sarah MacMillen, associate professor of sociology, said she doesn’t typically use textbooks in class.

“A lot of the time, what I try to do is pick original sources or novels which illustrate concepts that keep costs low for students,” MacMillen said.

But some professors make it difficult for students to rent textbooks or buy them used. Sophomore supply chain management major Kristofer Vucelich said he wants to purchase his books online, but a few of his professors require books with special access codes to online content.

“The books come with these stupid codes, and you can’t just buy the codes. You have to buy the package deal,” Vucelich said. “So you have to spend double the money and buy it new.”

Another option that might catch on soon is open-source textbooks, which are faculty-written, peer-reviewed and created under an open license. The Student Public Interest Research Groups tested the books at five colleges earlier this year and found that switching to open-source books could save students $128 a course.

The alternative methods of purchasing textbooks – renting, buying used and using open-source books – haven’t made a significant dent in the new hardcover textbook market yet, which is controlled by publishers such as McGraw Hill, Cengage and Pearson. According to the Association of American Publishers, textbook publishers recorded $4.9 billion in revenue in 2014, down from $5.1 billion in 2012.

“Once people stop buying from them, they’ll be forced to lower the prices,” Daher said.