Marcela Mack

staff writer

11/19/20

Duquesne student Marcela Mack recently sat down with Carrie Teresa, the author of “Looking at the Stars: Black Celebrity Journalism in Jim Crow’s America.” The book, and the conversation below, is an insightful and informative look at the Black press dating back to times of segregation without the efforts of the Black press.

The conversation with Teresa has been edited for brevity and clarity.

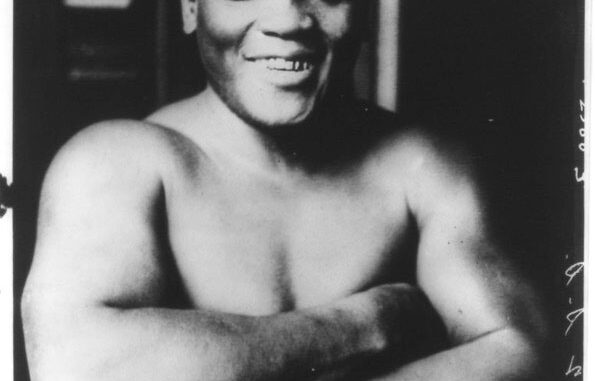

Carrie Teresa: I had never learned about Black press journalism, so I had no idea that newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier existed. I knew a little bit about the abolitionist press pre-Civil War, but I didn’t know that these newspapers extended beyond the end of the Civil War to have these kinds of readerships that they had. I was so enamored with the editorial style and the approach to reporting and the investigative work that these newspapers did. That semester, as I was studying the Black press and trying to figure out exactly what I wanted to do with it, my husband, who is a huge sports fan, convinced me that we should watch the six-hour documentary on Jack Johnson.

Unforgivable Blackness is a Ken Burns PBS documentary that I had absolutely no interest in watching, because I am not interested in sports. On a rainy Saturday night, he finally kind of convinced me that we should sit down and watch it, because he knew I was interested and had always been interested in African-American culture, and the cause for civil rights. That was something I had always carried with me, and was probably why I fell so in love with the Black press. We sat down and watched the documentary, and I fully expected to fall asleep. And I did not. I was completely riveted by Johnson’s story. I was riveted by the idea that he was as popular as a mass market celebrity, as he was in a time when we really didn’t have mass market entertainment mechanisms.

We had newspapers, we had some film — not much — we didn’t have TV, we didn’t have radio. We didn’t have all the mechanisms of celebrity that makes celebrities so ubiquitous now in 2020, but yet Johnson was essentially being a household name and being this sort of larger-than-life character. He was a pioneer in sport. He was the first Black heavyweight champion of the world.

I just kind of fell in love with the idea of looking at journalistic coverage of Johnson through the eyes of the Black press, because Johnson, as an African-American celebrity who did whatever the heck he wanted, including traveling with groups of white women, and gambling, and carousing and carrying on. I kind of knew what the mainstream press thought of him and that was covered in Ken Burns’ documentary. The racist mainstream coverage of Johnson was really no surprise to me at all. And I wasn’t particularly interested in that. I was really interested to understand what Black fans and Black journalists thought of Johnson in his time, because he was such a ubiquitous celebrity.

Because he was such a controversial character, I thought that was just a really interesting cultural question. I realized how much I enjoyed going through the archives and reading Black press newspapers. I’m a student of popular culture, everyday culture. I’m a celebrity gossip kind of follower – just in my private life. So the prospect of following other celebrities, essentially in the gossip pages of these newspapers, seemed like this really kind of novel topic to cover for my dissertation.

And so that’s what I did. I expanded my approach in looking at the framing of Johnson and Black press newspapers to include an inductive reading of Black person newspapers for a 40 year period, 1900 to 1940. So what other celebrities were famous during that period and to figure out how they were covered if they were celebrated by Black journalists and fans, if they were criticized, um, you know, what were the repetitive frames that kept coming up over and over again? And how could those frames help us to understand how Black celebrity culture works today? So once my dissertation was done in 2014, I got a book contract with the University of Nebraska press. I spent two years editing the project, and it came out as “Looking at the Stars,” in 2019.

Q: It’s really interesting, the contrast of the story that the mainstream media does, and then the story that the Black press displays. Did you find with every certain celebrity that you would look into that there were always those stark differences?

Teresa: I really wanted to avoid doing a comparison between mainstream media and Black press media. Until very recently, the way we’ve thought about Black celebrities has been this color line trope, the idea that a Black celebrity doesn’t have any cultural value until they get the attention of the mainstream press. And I hate that idea. I wanted to throw that idea out all together because the underlying assumption of that is racist. It’s a racist ideology. It’s the idea that the only thing that has value is what white America assigns it to have value.

I wanted my work to be as far away from that as possible. So I made the conscious decision to not look at any mainstream press coverage at all, and to focus only on the Black press with the proposition that the most important Black celebrities of the time were the Black celebrities of the Black press covered and that they celebrated and provided as exemplary models for the Black communities during that period.

Those are the Black celebrities we should be talking about today in 2020. Those are the people who should have statues and public commemorations of them. Those are the folks that are truly important. Some of those people overlap with the mainstream pioneers of Jack Johnson, Hattie McDaniel, Bert Williams, Jesse Owens and Joe Lewis. Those people are incredibly important, they just happened to get mainstream attention. It doesn’t mean that they are more important than the folks who never did. So I never looked at mainstream newspapers as a result.

Q: There definitely is an opinion of where there’s mainstream, and then Black media, where it all really should just be one and not have prerequisites for you to be included in the main picture.

Teresa: I never liked that idea, and I was never comfortable with that idea.

Especially back in the early 1900s — which is my time period — there was absolutely no diversity in mainstream news outlets. We’re operating under the Jim Crow regime of segregation and discrimination. We didn’t start to see newsrooms diversify until the civil rights movement. Even today, if you look at the numbers from like the Pew Research Center, newsrooms are not nearly as diverse as they need to be to reflect their readership and America’s population — they’re still predominantly white and male. So there’s no way that those newsrooms, populated the way that they are, can tell the story properly of new subjects who don’t look like them and share their experience.

Q: What kind of impact do you feel that the representation of Black celebrities has on the history of celebrity journalism as a whole?

Teresa: Because of Black press coverage of Black celebrities, celebrity journalism as a whole has some social consciousness. What that means is that when celebrity journalists cover their subjects, they have some frame of understanding of why they might have an obligation, or a passion for social justice causes. Because we have this frame of entertainer activists from the Black press, we have some way to understand and to cover with folks like Beyonce, who are not only incredibly talented artists, but who are very active philanthropists and cultural critics and activists. That is the lasting legacy of that coverage from the Black press, is that we actually have a frame to understand what an entertainer activist is, where they come from and what cultural function they serve for their readers and for their fans.

There’s less maybe of a question than there would be of, “why is this person talking? They don’t know what they’re talking about. They don’t belong in this conversation.”

There was that Fox News pundit who told LeBron James should just dribble, or some mundane offensive comment. James is obviously a really outspoken activist, and this amazing cultural force, as well as the most dominant basketball player on the court. So the idea that LeBron James, with all of his influence, all of his resources, all of his experience navigating his career and his life wouldn’t have a say in American culture and politics is just outlandish.

Q: How can the early days, all the way from the Jim Crow era of celebrity Black journalism, translate to today’s social media age of journalism?

Teresa: I can tell you, it still thinks that the mainstream press has a long way to go largely because of that newsroom diversity issue. From what my students have reported, and from what I see them share on Facebook and Instagram, I know that the Internet has opened up spaces for diverse voices to share viewpoints and to share experiences that otherwise wouldn’t be available through the mainstream press gatekeepers.

I think that that’s a really positive thing. I see students retweet stuff and share stuff from things like the shade room and other sources that seems to be this kind of collection of exclusively online sources that are grassroots in nature, that people gravitate towards for this coverage. I think that’s a marvelous thing.