Eliyahu Gasson | Staff Writer

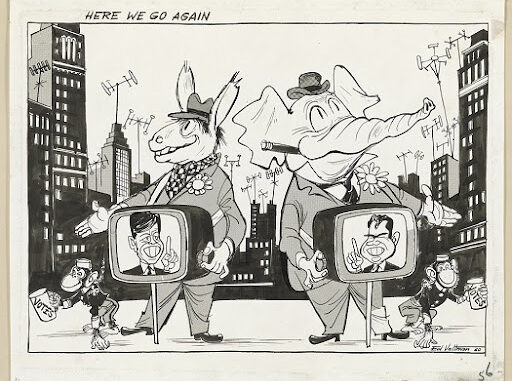

In the realm of politics in the United States, the spectacle of televised political debates has become a staple. The first of these debates was in 1960 when Democrat John F. Kennedy and Republican Richard M. Nixon took the stage to make their cases on CBS.

The medium supposedly offers voters a crucial glimpse into the minds and policies of potential leaders. However, with a bit of critical thinking, it becomes clear that these debates do not have as much influence on voters as we believe them to have.

Take the 2016 election, in which Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton stood as the candidates for their respective parties. Their unique personalities and controversial campaigns were new to mainstream politics. Trump’s rhetoric was far cruder than the average Republican politician up to that point. Who else on the GOP primary stage would have called Ted Cruz’s wife ugly on social media, or callously say this about the late Senator John McCain, a former prisoner of war: “I like people who weren’t captured?”

In the case of the 2016 election cycle, having Trump on stage arguably caused terrible damage to political discourse in the U.S., not improved it.

According to a study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the prevailing sentiment among voters is often that they have already made up their minds before the debates even commence.

The study found that if a person remains undecided by the time debates start, it is plausible that they were never fully committed to voting in the first place. In essence, the debates become a redundant exercise for a substantial portion of the electorate. The recent third GOP primary debate served as a clear and effective example of this.

Despite the absence of Trump, the front-runner for the party since the beginning of the race, the remaining candidates failed to significantly alter the established order of popularity. Per the latest polling from FiveThirtyEight, the GOP candidates’ standings remain relatively stable, affirming that these debates do little to sway the preconceived notions voters may already harbor.

Granted, the second GOP debate may have had some effect on the GOP primary. Almost a month later, former vice president Mike Pence dropped out of the race and former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley overtook Vivek Ramaswamy by 2.2 percentage points.

Televised debates are no more than UFC fights for political science enthusiasts. They act similarly to sporting events in that they are unscripted, games with referees who make sure the players stick to the rules. Does a Steelers fan decide to start rooting for the Ravens when the former loses a game to the latter? Do people who are undecided on what team they support suddenly pick a side that they stick with for the rest of the campaign when one does better than the other?

Typically, the answer to both cases is no.

As we reflect on the enduring saga of televised debates in the American political arena, it’s hard not to question the assumed weight we place on what are essentially rhetorical blood sports.

We’ve seen it in the inaugural Kennedy-Nixon showdown in 1960, the tumultuous clash between Trump and Clinton in 2016 and the anticlimactic GOP primary debates of 2023.

These spectacles have been cast as pivotal moments in the path to the presidency while critical analysis suggests that debates at best do little to change the political landscape, or at worst, lead to further deterioration of civil discourse in the realm of politics as a whole.