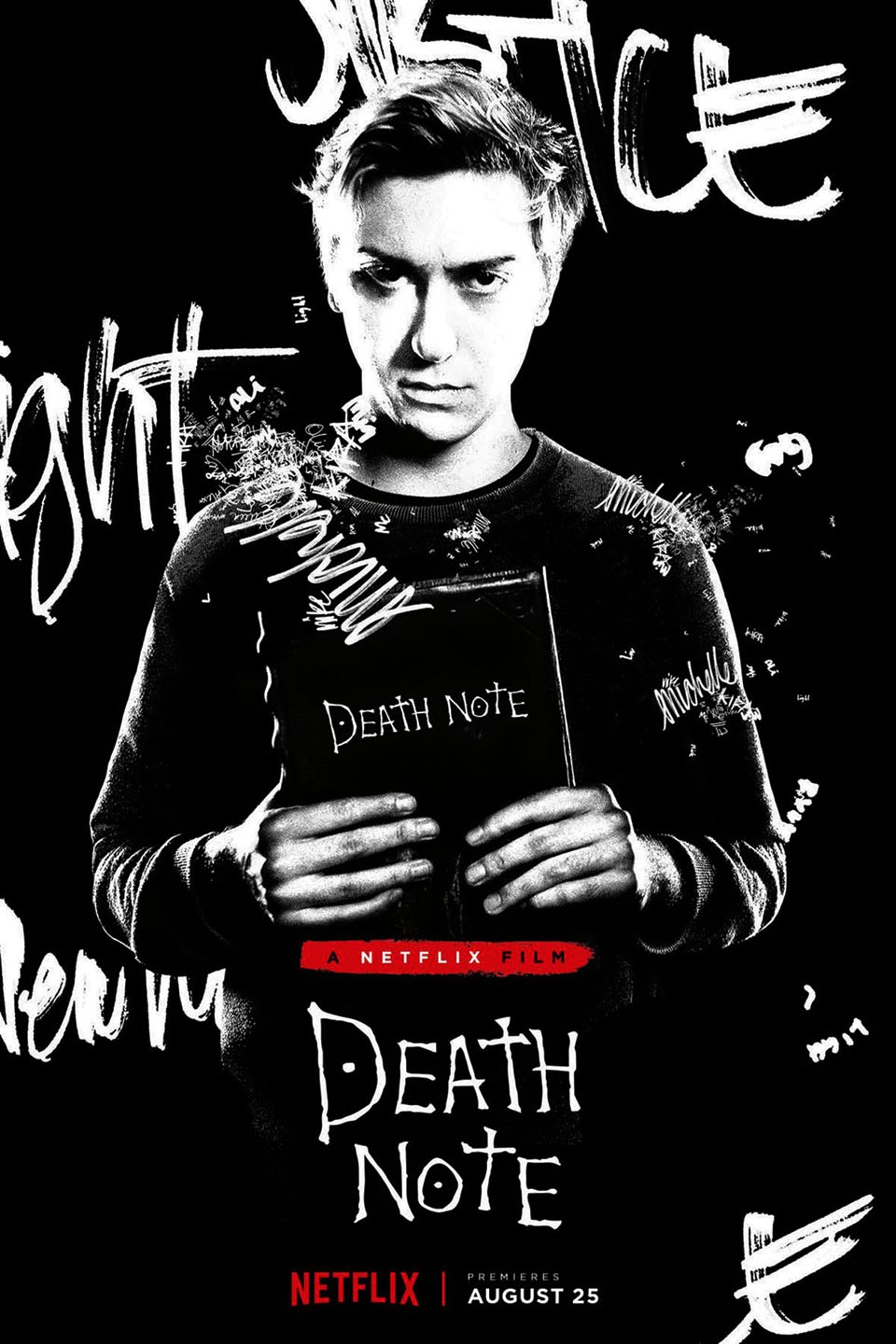

The original ‘Death Note’ manga first appeared in ‘Weekly Shōnen Jump’ in Dec. 2003. It has been adapted into a novel, an anime, a game and other movies.

By Liyang Wan | Staff Writer

The new movie adaptation of the hit manga series Death Note has certainly made a name for itself. Specifically, this movie has courted controversy since its announcement, and some reactions have been particularly critical.

Fans of the original series have been critical of the casting for this adaptation, claiming that it is discriminatory and part of a wider problem of whitewashing, or the casting of white actors in the place of historically or contextually non-white characters, in Hollywood. Some are even protesting the film.

The director, Adam Wingard, has defended his casting choices and story changes. In an interview with RadioTimes.com, he claimed the changes he made to the property are a part of the adaptation process to make it fit in an American frame of reference. As such, actors Nat Wolff and Margaret Qualley play Light Turner (otherwise known as Light Yagami in the original series) and Mia Sutton (Misa Amane in the manga). Another important character “L” is played by Lakeith Stanfield.

Regardless of one’s opinions on the casting, there are other qualities about Death Note worth examining. Its plot is one such thing. No matter the quality of an adaptation, most of Death Note focuses on the battle of wits between the protagonists Light and L, with criminal justice being a selling point for this series.

However, this new version feels simply like a movie with a teenager’s love story and horror elements thrown in. The U.S. version abandons the thoughtful plot of the original story, instead borrowing its utmost basic premise: Light accidentally acquires a supernatural notebook, and he starts to use it for killing bad guys whose name and face he knows. L has to stop him. The focus isn’t even on the conflict between Light and L in the adaptation. Rather, the only outstanding aspect of the film is the bloody killings. Instead of the “cat-and-mouse” game Wingard praised the original for, the selling point is to see how characters kill people and the horrific spectacle of their deaths.

I suppose the emphasis on brutality is reasonable considering Wingard’s roots as a horror film director. Within his work, violence and viscera feature heavily. However, gore is clearly not the key element of Death Note. In the original version, many people are set to die due to heart paralysis, for example, which is a very “friendly” death compared to someone’s head exploding in the new adaption. The point of Death Note, what makes it so popular, is the intrigue and detective work, not death.

Another problem is character design. Wolff’s Light is a far cry from the original. Although he is smart, he’s also weak and somewhat a loser at school. Predictably, the movie treats his acquisition of the titular book as a way to compensate for his deficits rather than creating a crisis of character. Moreover, Light even uses the Death Note to hook up with the school cheerleader, Mia. Compare that sub-standard depiction to the original Light, a genius college student who is as bold as he is popular. He even dares to kill his own father in order to win over L.

Speaking of L, his U.S. version does try to imitate the original, replicating little quirks such as loving sugar and crouching in chairs. However, he, too, received a massive overhaul. For example, American L takes a gun to his confrontation with Light to threaten him, an act totally opposite with his original depiction. Even his detective work is downplayed in this remake, further gutting the appeal of Death Note.

Mia Sutton (Margaret Qualley), as compared to Light and L, is the surprising highlight in this version and cements herself with a critical role. Without going too much into it, suffice it to say that Mia asserts herself more than her manga counterpart, though her fate at the end of the movie is puzzling, to say the least. The best I can assume is that it’s a hook that the director left for the sequel.

All told, Death Note is a far cry from its source material. Sometimes, Hollywood remakes can be quite unexpected and unrealistic, especially if it involves this type of cross-cultural reproduction. It is not easy to grasp or understand the essence of a different culture, and unfortunately, the filmmakers here could not get the point, leading to a rather nondescript film.

It must be said that Death Note, as a property, spans numerous comics, anime and movie adaptations. It has a large number of fans from around the world, but Netflix and Wingard apparently did not take these fans seriously. The result is clear, with an abysmal product and an equally abysmal critical and popular response.